Arthur R. Butz archive

The Hoax of the Twentieth Century

Supplement 5

Vergasungskeller

[Webmaster note: Formerly Appendix F]

An early version of this supplement appeared in the Journal of Historical Review, vol. 16, no. 4, July-Aug. 1997, pp. 20–22.

Veteran revisionists recognize that an outstanding small problem has been the Vergasungskeller

that was evidently in or near Crematorium II in the Birkenau part of the Auschwitz camp.

Crematorium II (and its mirror image Crematorium III) had two huge underground morgues, Leichenkeller 1 (LK 1) and LK 2, and a smaller morgue LK 3. LK 1 and LK 2 were simple concrete morgues in which bodies were simply laid on the floor. See Fig. 33. Essentially everything said here concerning Crematorium II should be presumed to hold also for Crematorium III. With one exception to be noted, nothing said here applies to Crematorium I (in the Stammlager part of the Auschwitz camp, rather than Birkenau, and taken out of service in July 1943). Apart from remarks near the end about the work of Samuel Crowell, nothing said here applies to Crematoria IV or V at Birkenau.

A letter to SS headquarters Berlin, from the Auschwitz construction department, dated 29 January 1943, when the construction of Crematorium II was nearing completion, reports that frost prohibits removal of the formwork for the ceiling of the Leichenkeller

(without specifying which of the three is meant) but that this is unimportant, since the Vergasungskeller

can be used for that purpose, i.e. as a morgue. The document had the number NO-4473 at the Nuremberg trials. Specifically, NO-4473 reads:

The Crematorium II has been completed — save for some minor constructional work — by the use of all the forces available, in spite of unspeakable difficulties, the severe cold, and in 24 hour shifts. The fires were started in the ovens in the presence of Senior Engineer Prüfer, representative of the contractors of the firm of Topf and Sons, Erfurt, and they are working most satisfactorily. The formwork for the reinforced concrete ceiling of the Leichenkeller could not yet be removed on account of the frost. This is, however, unimportant, as the Vergasungskeller can be used for this purpose.

The firm of Topf and Sons was not, on account of the unavailability of rail transport, able to deliver the aeration and ventilation equipment on time, as had been requested by the Central Building Management. As soon as the aeration and ventilation equipment arrive, the installing will start so that the complete installation may be expected to be ready for use by 20 February 1943.

A report of the inspecting engineer of the firm of Topf and Sons, Erfurt, is enclosed.

When NO-4473 is interpreted with the help of some documents reproduced by Pressac,[212] it is shown that the Leichenkeller

is LK 2. Pressac believes that the Vergasungskeller

is LK 1 and that a slip,

indeed enormous gaff

(sic), caused the author of the document to betray the true purpose of LK 1, referring to it as a gassing cellar

(although the usual German word for such a concept is Gaskammer

). On no known set of engineering drawings is a Vergasungskeller

indicated.[213]

Many of those who would have us believe that there were homicidal gas chambers at Auschwitz insist on this interpretation. An interesting exception has been the Austrian-born Raul Hilberg. He cites and even quotes from NO-4473 in the Killing Center Operations

chapter of The Destruction of the European Jews, but he is silent on the Vergasungskeller.

In my 1976 book The Hoax of the Twentieth Century, I offered that the Vergasungskeller was a part of the crematorium building devoted to generating a combustible gas for the ovens.[214] This interpretation was linguistically correct and could be technically correct, depending on the design of the ovens. The primary meaning of Vergasung

is gas generation or carburetion, i.e. turning something into a gas (a Vergaser

is a carburetor). A secondary meaning is application of a gas as in fumigation or in gas warfare. It is also the word Germans use today to refer to the alleged gassing of Jews; however, they use Gaskammer

rather than Vergasungskammer

or Vergasungskeller

for the facility imagined to have accomplished this. Such usage also applies in the literature on fumigation.[215]

By 1989, Robert Faurisson realized that my original interpretation was wrong, and later in 1989, Pressac[216] conclusively showed that it was wrong, based on the design of the cremation ovens. In 1991, Faurisson offered a theory[217] that the Vergasungskeller was a storage area for fumigation supplies within LK 3.

In 1992, I showed that there were many ways Vergasung

can come up in sewage treatment technology and offered that the Vergasungskeller might be found in the sewage treatment plant next to the crematorium. However, I favored the interpretation that the Vergasungskeller was simply a facility for generating fuel gas for the camp.[218] NO-4473 suggests, but does not require, that the Vergasungskeller was located within the crematorium building.

The purpose of this note is to offer another interpretation, which I now believe is more plausible than any earlier offered by me or anybody else. Before I do that, I should remark that the problem here is what the Vergasungskeller was, not whether it was a homicidal gas chamber. Those who claim it was a homicidal gas chamber focus their attention entirely on that one word in the document. If they would instead focus on what the document says, they would realize that it is impossible to make that interpretation work. The document shows that in January 1943 the Germans were in a great rush to use the building as an ordinary crematorium.

As Faurisson discussed earlier,[219] during World War II the combatants paid great heed that new structures be considered, if possible, as air raid shelters. There were two principal dangers that such shelters were to provide protection against: bombs and gas attacks. On account of World War I experiences, the possibilities of the latter were taken very seriously. Indeed, many simply assumed that gas would be used, despite treaties outlawing its use. Typically, a gas shelter was conceived of as a bomb shelter, preferably underground and very strong structurally, with some features added to make it secure against gas; a gas shelter had to be gas tight but allow people to breathe. Since in many cases it was not economic to provide such structures for at most only occasional use, it was recognized that such shelters could exist in the form of embellishments to structures that exist for other purposes. However, the number of suitable such structures was limited. For example, the typical underground cellar belongs to a building with several stories; the collapse of these in an air raid could prevent people from leaving the cellar.[220]

Germany started its air raid gas shelter program early with a 10 October 1933 decree of the Ministry of Finance providing financial incentives for the construction of shelters. The decree was followed by the Luftschutzgesetz (Air Defense Law) of 26 June 1935. Three German decrees in May 1937, in application of the Luftschutzgesetz, alarmed the British Chargé d’Affaires in Berlin, who compared the earnest German attitudes on air defenses to British apathy. The provision of shelters advanced far in Germany before the war, and of course was accelerated with the outbreak of war. On defense against gas, Germany was deeply committed to the shelter approach in its civil defense program, in contrast to the British, who put more emphasis on distribution of gas masks. However, it should be stressed that in World War II thinking, bomb and gas defenses went together, and provision of the one was unlikely without the other.[221]

Since the 1991 Persian Gulf War, Israel has had a law requiring that every newly constructed domicile have a room equipped as a gas shelter.[222]

My proposal is that the Vergasungskeller was a gas shelter. It need not have been located within Crematorium II, but I believe it most likely was, on account of the fact that Crematoria II and III, with their large concrete cellars, were obviously ideal for adaptation as air raid shelters. Indeed, when this problem is looked at from the point of view of defense against air raids it seems there was no better choice at Auschwitz. The German authorities responsible for providing air raid shelters would have insisted that the necessary embellishments be made to these structures, which were far more suited to such purposes than, e.g., Crematorium I at the Stammlager, which despite being above ground was converted to an air raid shelter after it was taken out of service as a crematorium in July 1943.[223] My reading of some of the relevant chemical warfare literature convinces me that Crematoria II and III were conceived of by the Germans as having this additional role.

I have never seen the word Vergasungskeller

in a lexicon; indeed I have seen it only in discussions of NO-4473![224] I have seen two German-Russian dictionaries, one a military dictionary, that say Gaskeller

means gas shelter.

[225] However, we should not consider ourselves bound to dictionaries on this. If one asks the question: In a World War II military context, what might Vergasungskeller

and/or Gaskeller

mean? I think that gas shelter

is the answer that comes naturally to mind and that other meanings are somewhat strained. Of course, other meanings come naturally to mind in non-military contexts.

As a personal example, I can report that I have been unable to find the term control lab

(or control laboratory,

controls lab,

controls laboratory

) in my IEEE Standard Dictionary of Electrical and Electronics Terms (edition of 1972), although every university Dept. of Electrical Engineering in the USA has a control lab,

and that is how we normally refer to such a place. I have also been unable to find the term in an unabridged Webster’s, in an on-line version of the Oxford English Dictionary, and in several other dictionaries I have.

If this interpretation of the Vergasungskeller of NO-4473 is correct, then we should view all three cellars in Crematorium II as air raid shelters, with only one being provided with the additional measures to make it effective as a gas shelter. That could only be LK 1, since NO-4473 implies it is not LK 2, LK 3 was very small and, conclusively, because LK 1 was the only one of the three provided with a gas-tight door.[226] Moreover, while all parts of the building had motor driven air extraction systems, it appears that only LK 1 had a motor driven air intake system.[227]

The extermination legend claims that homicidal gas chambers existed at Auschwitz and employed the pesticide Zyklon B, which releases HCN gas (hydrogen cyanide). Pressac also believes the Vergasungskeller was LK 1, but he interprets it as a gas chamber employing Zyklon B. Under my theory, he is then right on location but wrong on function. LK 1 had the basic features of a gas shelter.

Pressac admits that the air exhaust (at the bottom) and air intake (near the top) systems of LK 1 were misplaced for a gas chamber employing HCN.[228]

The reader should understand that here I am only considering the physical details of the construction of LK 1 that oblige us to interpret it as a gas shelter rather than gas chamber. There is much more evidence that LK 1 was not a gas chamber. The purpose of this note is only to interpret the word Vergasungskeller

as used in one document.

Why would the author of NO-4473 not refer to a Leichenkeller as a Leichenkeller? I don’t think a slip is involved. We normally do not consider ourselves bound to use only formal designations. More commonly, we refer to things according to their function or in any case the function that happens to be in mind at the time. The gas shelter features of LK 1 were its principal structural distinction from LK 2, and those features were being taken into account in the construction at the time. It was natural that LK 1 might be referred to as the gas shelter.

As another example of a use of terminology suggested by function, the engineers Jährling and Messing referred to LK 2 of Crematoria II and III, during construction, via the terms Auskleideraum

and Auskleidekeller

(undressing room or cellar), another one of what Pressac considers slips

that betrayed a criminal purpose.[231]

It seems hard to believe these were slips,

because they were so frequently committed. Jährling used this designation in a document of 6 March 1943, and then Messing used it in three documents later in March. If these were slips,

it would seem that by this time the bosses would have told them to clean up their language. They evidently didn’t, because Messing used the designation in two more documents in April.[232]

The truth about the undressing is much more prosaic. Pressac believes that, when the Germans viewed Crematoria II and III as ordinary crematoria, then the sequence of processing bodies was contemplated to be LK 3 to LK 2 to LK 1, but that LK 3 was eventually eliminated from the regular sequence.[233] However that may be, if the dead bodies were contemplated to start in LK 2, they would then be undressed there.[234] They would be stored in LK 1 while awaiting cremation. Presumably, LK 3 was only used when a body needed some sort of special processing, e.g. dissection or the famous extraction of gold fillings from teeth.

I am struck by the humorous simplicity of the theory offered here.

In March 1997, Samuel Crowell also proposed an interpretation of LK 1 as a gas shelter that goes far beyond, and in some respects departs on secondary levels from, the interpretations proposed here. Crowell’s theory is to be found at the Web site of CODOH (Committee for Open Debate of the Holocaust)[235] and since 2011 even as a book.[236] He went beyond my theory in two principal respects. First, he attributed to Crematoria II and III a broader role within the air raid/gas shelter paradigm. For example, showers and undressing are interpreted by him in terms of decontamination,

a feature of that paradigm. Second, he interpreted features of Crematoria IV and V in terms of air raid and gas shelters, matters on which he cites much contemporaneous German literature. Crowell has bitten off a big piece, and evaluation of his theories will take time. I believe he tends at points to over-hasty interpretation in terms of air raid and gas shelters, without adequate consideration of alternative interpretations, but my hunch is that he is mostly right.

Vergasungskeller R.I.P.

The Nuremberg trials document NO-4473 (the Vergasungskeller

document) has been a nagging problem for decades. My original interpretation, first published in 1976, of the document is retained here in Ch. IV for historical reasons. That interpretation, though technically and linguistically correct, turned out to be wrong. A second interpretation was probably wrong.[237]

The third interpretation, which led directly to the final interpretation I offer here, was that the Vergasungskeller was a gas shelter, constituting a secondary usage of what was otherwise a Leichenkeller (morgue) in the crematorium. I refer the reader to my 1997 paper[238] presenting that third interpretation, whose web version[239] first appeared in August 1996, and which is retained here as Supplement 5. I documented that the meaning of the word Gaskeller

is, or at least was in a military or civil defense context, gas shelter.

However the word in the document is Vergasungskeller,

and criticisms[240] of my gas shelter interpretation raised linguistic objections. For example, the delousing gassings elsewhere at the camp were done in a Vergasungsraum.

[241] Shortly after the appearance of my gas shelter interpretation of NO-4473, the theory that the crematoria were designed and built with air-raid and gas attack defense in mind was presented in depth and breadth by Samuel Crowell.[743] However even Crowell expressed discomfort to me over such an interpretation of the word Vergasungskeller,

but I believed that even his research left little room for any other interpretation.

Much of the difficulty has been that the word Vergasungskeller

has no established meaning. I have seen it only in NO-4473 and in discussion of that document. The apparent failure of the Germans to use the word forced us to make only speculative interpretations of its meaning. Vergasung,

alone, means either converting something into a gas, as in a carburetor, or applying a gas to something, as in a delousing chamber or in battle. All we can be sure of is that a Vergasungskeller is to be thought of as a below-ground-level facility relating to such activities, and therefore it could, as far as I could see in 1996, mean an underground shelter to retreat to in the event of an enemy attack involving or generating gas. At that point I was not trying to replace the word Vergasungskeller with Gaskeller, but now I am trying to effect the replacement or at least make an equivalence, for good reasons I shall present.

Another difficulty in interpreting NO-4473 is best appreciated by an engineering professor, and I am one. Engineers are very sloppy with words. To give an example I like to call to the attention of electrical engineering students, consider that in the basic courses we stress for students the difference between current and voltage, and the need to not confuse the two. We also teach that DC

means direct current, and AC

alternating current. Then they hear, from seasoned electrical engineers and electricians, and without apology, oxymoronic terms such as DC voltage

and AC voltage.

Thus the Vergasungskeller could be just sloppy wording.

The case that the Vergasungskeller can be interpreted as a clumsy reference to a Gaskeller can be supported by accepting something that the orthodox historians have claimed, and a document posted by the Buchenwald museum. This final (I assume) interpretation was posted on the web in 2007[242] and this Supplement essentially presents that interpretation, supplemented by more recent work by Samuel Crowell, who has done valuable work in this area. Earlier interpretations should be considered obsolete.

I note in passing that the first known interpretation of features of an Auschwitz crematorium, in terms of gas and bomb shelters, was offered by the late Dr. Wilhelm Stäglich.[243]

Vergasungskellerdocument

Gas shelters are routine as wartime defense measures, and the Germans were industrious in building them. Since the 1991 Persian Gulf War, Israel has had a law requiring that every newly constructed domicile have a room equipped as a gas shelter.[244] Moreover in 2010 Israel ordered gas masks distributed to all citizens, in a program to start in Feb. 2011, expected to last about three years.[245] However early in 2014 Israel announced that it will stop the distribution of gas masks.[246]

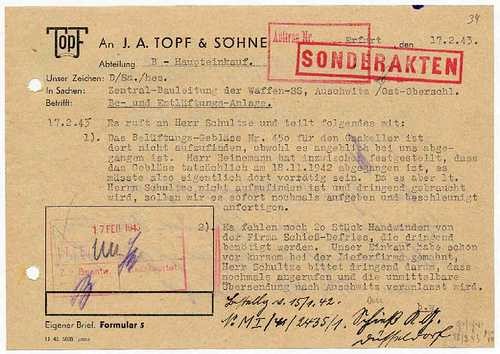

Only two months after my web posting, on 16 Oct. 1996, an anonymous article appeared in the French magazine L’autre Histoire. The author was understood at the outset to be Jean-Claude Pressac.[247] The article triumphantly announced (p. 13) the discovery of a Topf (crematorium builders) company document, dated 17 Feb. 1943, showing that there was a Gaskeller

in what was clearly Crematorium II at Auschwitz. Pressac interpreted the Gaskeller as a gas chamber. I assume he had not seen my slightly earlier posted article. Incidentally, if I had first seen the word Gaskeller out of useful context, then I, too, would have assumed it meant an underground Gaskammer.

Pressac’s Gaskeller document remained unpublished until 2005, when it was published by the Buchenwald museum, which had been bequeathed Pressac’s papers (Illustration 1). The matter is well summarized elsewhere.[248] The supervisors of the Buchenwald museum, contemporary Germans, think a Gaskeller

was an underground Gaskammer,

but during World War II it was a gas shelter, as Crowell has confirmed.[249]

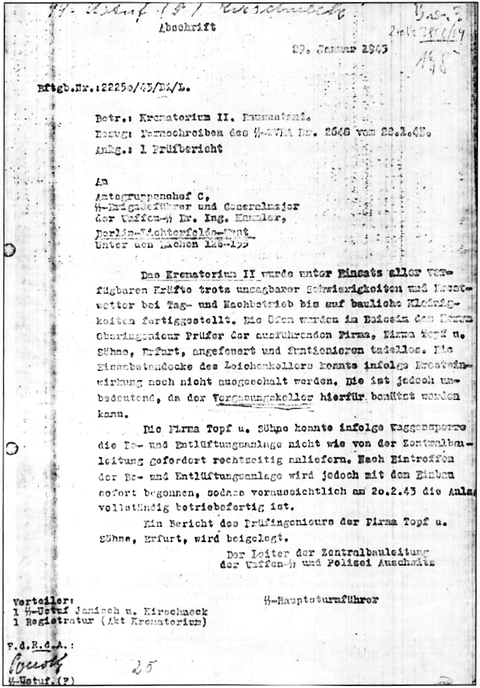

The document NO-4473 as it comes to us, the Vergasungskeller

document, is shown in Fig. 2 (copied from an anti-revisionist web site[250]). The orthodox interpretation of the handwritten notations, wherein the word Vergasungskeller

was underlined by hand and Kirschneck!

was written in the top margin, has been advanced by Robert Jan van Pelt, Deborah Lipstadt’s expert witness in the 2000 Irving-Lipstadt trial. According to his interpretation the notations were intended to draw Kirschneck’s attention to the underlined word because the use of the word Vergasungskeller

was a slip

that the authorities objected to, because it exposed the criminal intent of the building.[251]

The idea that the construction workers at Auschwitz engaged in a systematic masquerade to conceal evidence of mass exterminations, going about their daily business while figuratively winking at one another, is both a staple and a necessity of the Holocaust

legend, and I consider it completely ridiculous. Could I calculate that the burning down of New York City could be concealed by hiding the matches? Would I calculate that my accomplices would be equally diligent about those matches?

However, the interpretation of the hand notations as expressing objections to the use of the word Vergasungskeller

in the document is reasonable, and I wonder why it took me so long to see it. Those who accept the premise of van Pelt’s interpretation of the notations thereby also accept a hypothesis of my present theory, which is a clarification and reinforcement of the third interpretation

referred to above.

If we accept van Pelt’s interpretation of the notations — that the use of the word Vergasungskeller

was for some reason considered inappropriate and that in the opinion of the management at Auschwitz the word should not have been there — we are not obliged to accept van Pelt’s idea as to the nature of management’s objections.

It is reasonable to propose that something like Gaskeller

or Gasschutzkeller

should have been there, because the use of a related concept mitigates the document’s error, because there was in fact a Gaskeller there, because the author of the unusual word Vergasungskeller

could have had that meaning in mind, and because of the many other indications we have that the crematoria were designed and built with air-raid and gas attack defense in mind. Those are strong reasons.

Of course the relevant space was not a dedicated Gaskeller. It was primarily a Leichenkeller, i.e. morgue. It was common that bomb and gas shelters were provided in spaces primarily dedicated to other uses.

Carlo Mattogno does not accept the above interpretation of the handwritten notations, but he shows conclusively that the Vergasungskeller and the Gaskeller were the same thing.[252] He insists that both were for emergency disinfestation or delousing, despite his reference to an online source that reproduces the Gaskeller document as a reference to a gas shelter. It appears that his reason for designating the Vergasungskeller thus is that, in all other Auschwitz contexts in which he has seen Vergasung,

it means disinfestations. The reasoning doesn’t hold. For example, my original interpretation of the Vergasungskeller, as a facility to generate a combustible gas for the crematorium ovens, seemed linguistically correct to Wilhelm Stäglich, a highly literate German jurist.[253]

I have certainly gotten a good lesson on the perils of documents interpretation. We have been struggling, I since 1972, with an at least enigmatic document!

Revisionists should not apologize for a struggle with one document. The orthodox side dismisses or distorts huge mountains of documents. For example Ch. VII here reproduces German documents speaking only of emigration, expulsion, and resettlement of Jews, but that mountain of documents is waved away with a few words.

August 2014

Walter Schreiber on the ‘Gaskeller’

The following contribution appeared in 2000 under a pen name used by the accredited civil engineer Walter Lüftl.[254] Between 1990 and 1992, Lüftl was the president of the Austrian Federal Association of Engineers. Due to his prominence and his revisionist involvement[255] he managed to gain the trust of various individuals who would otherwise have remained silent forever due to their fear of persecution. Among them was also the court-appointed engineer who, during the 1972 Auschwitz trial in Vienna, submitted an expert report in which he determined that the rooms of the Auschwitz crematories which are said to have been homicidal gas chambers could not have been used for that purpose. This expert report was one decisive factor leading to the acquittal of the two defendants—the architects who had been responsible for the construction of the crematories. This expert report was never published, and today it can no longer be found in the case files. But Lüftl’s public support for revisionism motivated said expert witness to finally speak out. When Lüftl published this case in 1997, the public at large learned for the first time about this vanished document.[256]

The following interview was conducted by Lüftl with the superior of the two architects who sat in the dock in Vienna back in 1972: Oberingenieur Dr. Walter Schreiber. He, too, contacted Lüftl on his own accord and agreed to entrust to him his knowledge which he did not want to take to his grave. Since he had justified fear of persecution and prosecution, he refused to speak out during his lifetime about his knowledge of the crematories at Auschwitz.

Schreiber’s statements support the theses by Arthur Butz and Samuel Crowell that the morgues of Crematories II & III in Birkenau served as air raid shelters as their auxiliary function. This is why we reprint this interview here.

The Editor

Who is Walter Schreiber?

Walter Schreiber was born in 1908 and died in 1999 at the age of 91 in Vienna. He studied civil engineering at the Technical University in Vienna and worked first on the construction of the alpine high altitude road Großglockner-Hochalpenstraße

as assistant to the construction manager. After an extended period of unemployment he emigrated to the Soviet Union in 1932 and worked on the construction of refrigeration buildings and alcoholic beverage factories in Bryansk, Spassk, and Petrofsk until 1935. In 1936 Schreiber went to Germany, where he worked first for the Tesch Corporation and then, from 1937 to Aug. 31, 1945, for the Huta Corporation. Schreiber was employed as a senior engineer in the branch office in Kattowitz from Jan. 11, 1943, until the evacuation of Upper Silesia in 1945.

After the war Schreiber worked for the Municipal Construction Office Directorate (Stadtbauamtsdirektion) Vienna, the Austrian Danube Power Plants Society (Österreichische Donaukraftwerke AG), the Jochenstein Danube Power Plant Society (Donaukraftwerk Jochenstein AG) and the Verbundgesellschaft Vienna. After well-deserved retirement he lived in Vienna, mental capacity fully in tact, until his death.

Why is Schreiber Interesting?

What is so interesting in the professional life of this Austrian civil engineer? He worked as a senior engineer in the branch office in Kattowitz for the construction activities of his firm and was also responsible for constructions in the concentration camp Auschwitz and its sub-camps.

He was interviewed about Auschwitz in the year 1998 by Dipl.-Ing. Walter Lüftl, who had been President of the Austrian Society of Civil Engineers until 1992. Answers that are of interest for historiography are found in the following:

Lüftl: In which areas were you active?

Schreiber: As senior engineer I inspected the civil project of the Huta Corporation and negotiated with the Central Construction office of the SS. I also audited the invoices of our firm.

L.: Did you enter the camp? How did that happen?

S.: Yes. One could walk everywhere without hindrance on the streets of the camp and was only stopped by the guards upon entering and leaving the camp.

L.: Did you see or hear anything about killings or mistreatment of inmates?

S.: No. But lines of inmates in a relatively poor general condition could occasionally be seen on the streets of the camp.

L.: What did the Huta Corporation build?

S.: Among other things, crematoria II and III with the large morgues.

L.: The prevalent opinion (considered to be self-evident) is that these large morgues were allegedly gas chambers for mass killings.

S.: Nothing of that sort could be deduced from the plans made available to us. The detailed plans and provisional invoices drawn up by us refer to these rooms as ordinary cellars.

L.: Do you know anything about introduction hatches in the reinforced concrete ceilings?

S.: No, not from memory. But since these cellars were also intended to serve as air raid shelters as a secondary purpose, introduction holes would have been counter-productive. I would certainly have objected to such an arrangement.

L.: Why were such large cellars built, when the water table in Birkenau was so extremely high?

S.: I don’t know. Originally, however, above-ground morgues were to be built. The construction of the cellars caused great problems in water retention during the construction time and sealing the walls.

L.: Would it be conceivable that you were deceived and that the SS nevertheless had gas chambers built by your firm without your knowledge?

S.: Anyone who is familiar with a construction site knows that is impossible.

L.: Do you know any gas chambers?

S.: Naturally. Everyone in the east knew about disinfestation chambers. We also built disinfestation chambers, but they looked quite different. We built such installations and knew what they looked like after the installation of the machinery. As a construction firm, we often had to make changes according to the devices to be installed.

L.: When did you learn that your firm was supposed to have built gas chambers for industrial mass killing?

S.: Only after the end of the war.

L.: Weren’t you quite surprised about this?

S.: Yes! After the war I contacted my former supervisor in Germany and asked him about it.

L.: What did you learn?

S.: He also only learned about this after the war, but he assured me that the Huta Corporation certainly did not build the cellars in question as gas chambers.

L.: Would a building alteration be conceivable after the withdrawal of the Huta Corporation?

S.: Conceivable, sure, but I would rule that out on the basis of time factors. After all, they would have needed construction firms again, the SS couldn’t do that on their own, even with inmates. Based on the technical requirements for the operation of a gas chamber, which only became known to me later, the building erected by us would have been entirely unsuitable for this purpose with regard to the necessary machinery and the practical operation.

L.: Why didn’t you publish that?

S.: After the war, first, I had other problems. And now it is no longer permitted.

L.: Were you ever interrogated as a witness in this matter?

S.: No Allied, German, or Austrian agency has ever shown an interest in my knowledge of the construction of crematoria II and III, or my other activities in the former Generalgouvernement [German occupied Poland]. I was never interrogated about this matter, although my services for the Huta Corporation in Kattowitz were known. I mentioned them in all my later CVs and recruitment applications. Since knowledge about these facts is dangerous, however, I never felt any urge to propagate it. But now, as the lies are getting increasingly bolder and contemporary witnesses from that time like myself are slowly but surely dying off, I am glad that someone is willing to listen and to write down the way it really was. I have serious heart trouble and can die at any moment, it’s time now.

We are grateful to this contemporary witness, who asked us to wait to publish his testimony posthumously.

Other contemporary witnesses, like the SS-leader Höttl who also died in 1999, took their knowledge about the origin of the six million lie with them into the grave, without even caring whether the truth they held would at least be made known posthumously.

We will keep Herrn Dipl.-Ing. Dr. techn. Walter Schreiber in honorable memory.

Dipl.-Ing. Baurat h.c. Walter Lüftl